The mask is one of the oldest and most universal cultural expressions of humankind. Since ancient times, communities have sought in it a way to represent the sacred, the spiritual, and the symbolic. In Mexico, its creation constitutes an art deeply linked to indigenous roots and the syncretism that emerged after the Conquest. Through the work of the mask craftsman, not only a craft tradition is preserved, but also a cultural and family heritage passed down from generation to generation.

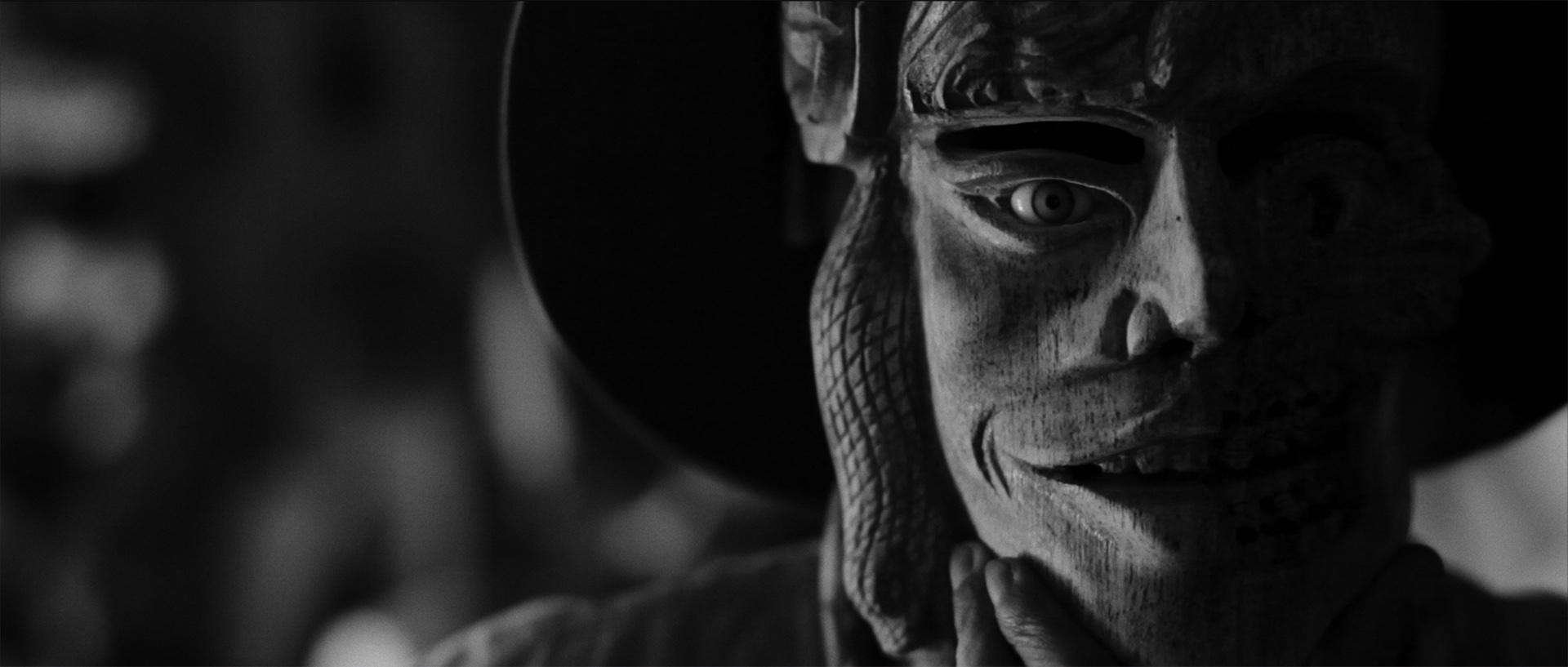

The Mexican mask craftsman does not limit himself to carving wood: he creates identities, bringing to life real or fantastic characters who participate in rituals, dances, and celebrations. The mask, by covering the face, reveals the soul of the people who wear it. It is a symbolic gateway between the human and the divine, between the visible and the invisible.

The shape of the masks usually comes from nature, they are mainly zoomorphic or anthropomorphic, the size takes into account human measurements, since the wearer must feel as comfortable as possible.

The mask as a cultural symbol

The mask has accompanied humankind since its earliest forms of ritual. In the Mexican context, it is associated with pre-Hispanic ceremonies that sought to connect with the gods or invoke the fertility of the earth. With the arrival of the Spanish, masks acquired new meanings, incorporating elements of the Catholic religion and giving rise to a syncretism that is still evident today in popular festivals.

Mexican masks are an essential part of community dances, carnivals, and theatrical performances. In each dance, the dancer embodies a character, a force, or a myth.

“Sometimes, male actors play female roles using masks. The reason for this is that in Europe, women were prohibited from acting or dancing; this same prohibition came to Mexico with the Spanish conquest.” / Ruth Lechuga; Chloe Sayer – Mask Arts of Mexico.

The variety of shapes and meanings is immense: there are masks that represent Europeans, Africans, indigenous people, animals, saints, devils, or fantastic figures. Each one reflects a local worldview. In them, the mask craftsman combines observation of the natural world with imagination, creating works where the real and the magical coexist.

Mask Carving: Technique and Art

Making a mask is a process that requires technique, intuition, and respect for materials. Wood is the most commonly used element due to its lightness and durability, although plant fibers, bones, feathers, and papier-maché are also used. Wood carving is not a mechanical act: the artisan selects the tree and cuts it.

In Naolinco, Veracruz, this tradition is kept alive thanks to artisans like Don Lino Mora, who has dedicated more than seven decades to carving masks for the Moors and Christians dance, celebrated in honor of Saint Matthew the Apostle. He preserves the tradition inherited from his ancestors by crafting these unique pieces from authentic wood from the region. The masks made in his workshop have been admired by national and international tourists, who buy his products and appreciate the craft he performs daily.

Don Lino Mora tells us that at age 11, he made his first mask in the image of a vampire, a character he saw in a costume worn by one of his uncles and that caught his attention. This is how he began his career, and he never imagined that it would be in newspapers or books, or that people from all over the world would visit him to enjoy and learn about his work. He considers his work a “great gift that God gave him” and that until now he has only “fulfilled the whim of creating and imagining for the client, and thus has continued to improve every day.”

With nearly 70 years of experience carving wood and letting inspiration flow through his mind, Don Lino Mora brings joy to the festivals and carnivals of Naolinco with his work. He creates masks for the characters of the Pastorelas: hermits, shepherds, devils, and Pilate; for those who appear in patron saint festivals, such as Moors, Christians, Saint James, and Black people. He creates special pieces, both in size and type, at the request of museums and collectors.

Don Lino is known as the best artisan in the area, and he prepares tirelessly so that hundreds of people can wear their finest masks on September 21st during the Patron Saint Religious Festival of this city, which boasts extraordinary natural beauty like its famous waterfall. Here, the cold embraces you and the warmth of the locals welcomes you, sheltering you and surrounding you with exquisite dishes such as mole, dulce de leche and jamoncillo, orange liqueur, cocadas (coconut sweets), pork cheeses, chiles rellenos (stuffed peppers), and sausages, until you are won over by the aroma, creativity, and design applied to the freshly processed leather used to make items such as wallets, belts, jackets, bags, and shoes, among others.

Masks and Cultural Syncretism

During the colonial era, masks were used by missionaries to teach Christian dogmas to the indigenous peoples. However, far from disappearing, communities adapted this element to their own beliefs, giving rise to a unique hybrid art form. As a result, masks became instruments for representing biblical passages, indigenous stories, and local legends.

Today, Mexican masks reflect the country’s ethnic and cultural diversity. They represent the three great roots of Mexican history—indigenous, European, and African—and, in some cases, also Asian history, especially on the Pacific coast.

“The mask is a ceremonial object that man uses to identify with deities and figures of his culture, closing the magical-religious cycle through which he invokes benefits or pays tribute to his gods and heroes” / María Teresa Pomar (Art Historian)

This quote highlights the spiritual value of mask-making: each piece is an offering, a vehicle for maintaining communication between the human and the divine.

The Family and Community Value of the Craft

In many Mexican communities, mask-making is a family craft passed down through generations. Knowledge is not taught in schools, but in backyards and workshops, through observation and practice. Children grow up surrounded by the smell of freshly cut wood and the sounds of the chisel, learning not only a technique, but also a way of understanding the world.

The mask craftsman works for his community. Each commission has a ritual purpose: it may be a promise, a thank you, or the preparation of a dance. Thus, the mask is not a commodity, but an object of collective identity, made with faith and respect. Buyers—local or visitor—do not just acquire a handcrafted piece, but a story, a living part of Mexican culture.

In Mexico, mask-making is a manifestation that transcends the material to delve into the spiritual. Through wood, artisans sculpt the soul of their people, giving life to beings that dialogue between history and imagination. This art, inherited and shared within families, is an expression of identity, resistance, and cultural continuity.

Each mask tells a story: that of the artisan who creates it, that of the dancer who wears it, and that of the people who celebrate it. They hold the memory of Mexico, a country that has managed to preserve in its traditions the living imprint of its past and the creative force of its communities.

References

- Lechuga, R., & Sayer, C. (1994). Mask Arts of Mexico. Chronicle Books.

- Pomar, M. T. (2006). Mexican Masks: Ritual Faces. National Institute of Anthropology and History.

Wooden Masks and Sculptures

Lino Mora Rivera

Dr. Miguel Ángel Dorantes Cabañas Street No. 22, C.P. 91400

Naolinco, Veracruz, Mexico

Cell: +52 (279) 104 25 44

Cell: (+52) 229.527.07.92 (Jesús Darío Mora Oliva, Jr.)

Email: linomascaras_mora@outlook.com.mx / rnb_mora@hotmail.com