A codex is a type of ancient manuscript, created before the invention of the printing press, that generally spans up to the end of the Middle Ages, as well as the pre-Columbian period and the conquest of the Americas. These texts record significant information related to their eras, especially historical and religious data. Physically, a codex consists of quires that are glued and sewn together, with pages written on both sides.

The etymology of the word “codex” comes from the Latin “codex,” which appears to be a reduction of “caudex,” meaning “trunk.” Originally, this term referred to the wax-covered wooden tablets that the Romans used as writing surfaces. Over time, the term was adopted to refer to books with pages, contrasting with scroll-shaped manuscripts, such as papyrus scrolls.

Since the advent of writing, humankind has left records on a variety of subjects. However, preserving written records has become complicated, especially those made on fragile materials like papyrus or parchment. Therefore, the versions that have survived to the present day are generally transcriptions made later.

The transition from scroll to codex in the Mediterranean influenced the format of the modern book; although Mesoamerican codices followed their own pattern, they contribute to showing the diversity of human solutions for organizing information.

Before the invention of the printing press, every book had to be handwritten by scribes, who were responsible for manually copying the texts. This made access to books a complicated and expensive process. The most common writing methods from the 1st century onward included codices and papyrus scrolls, although from the 4th century onward, Christian authors began to primarily adopt the codex format for transmitting religious literature, relegating the parchment scroll to a secondary role.

During the Middle Ages, codices became the predominant format for recording history, even after the discovery of America, where pre-Columbian peoples such as the Maya were already producing their own writings. A notable example is provided by Bernal Díaz del Castillo, who mentions the existence of paper books creating a detailed record of the rents brought to Moctezuma.

“His chief steward was a cacique whom we named Tapia, and he kept accounts of all the rents brought to Moctezuma, with his books, made of paper, which is called amal, and they had a large house full of these books.” / Bernal Díaz del Castillo

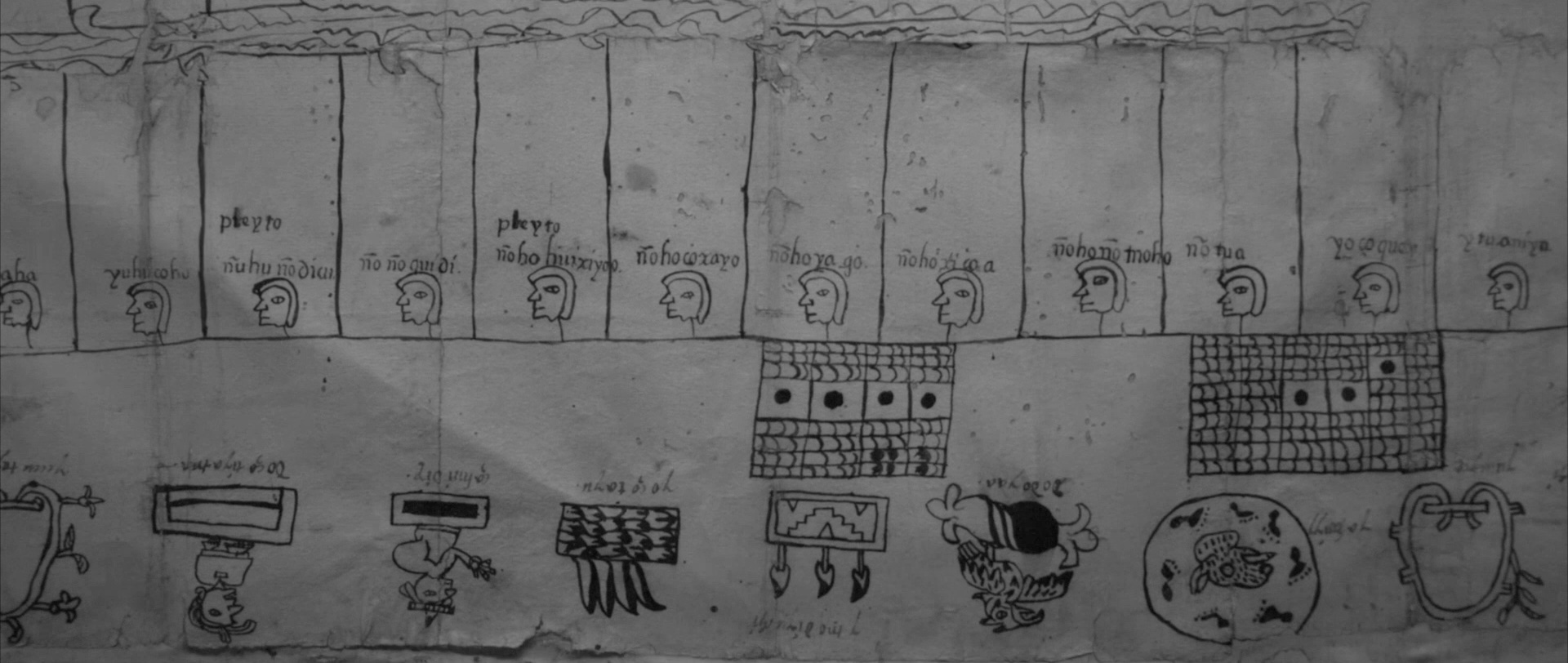

These manuscripts contain a wide variety of historical texts on migrations and settlements, native genealogies and the boundaries of their territories, the account of the arrival of the Spanish, and the social and political reorganization of Indigenous populations and their relationships with Spanish authorities and institutions. This led to numerous complaints and lawsuits, resulting in a wealth of documentation.

Thus, in world history, the codices represent one of the most significant turning points in the development of knowledge. Their global relevance includes the preservation of knowledge, the construction of identity, and their status as World Heritage.

From Egyptian papyri to medieval codices, manuscripts have allowed the transmission of scientific, literary, and religious ideas for centuries.

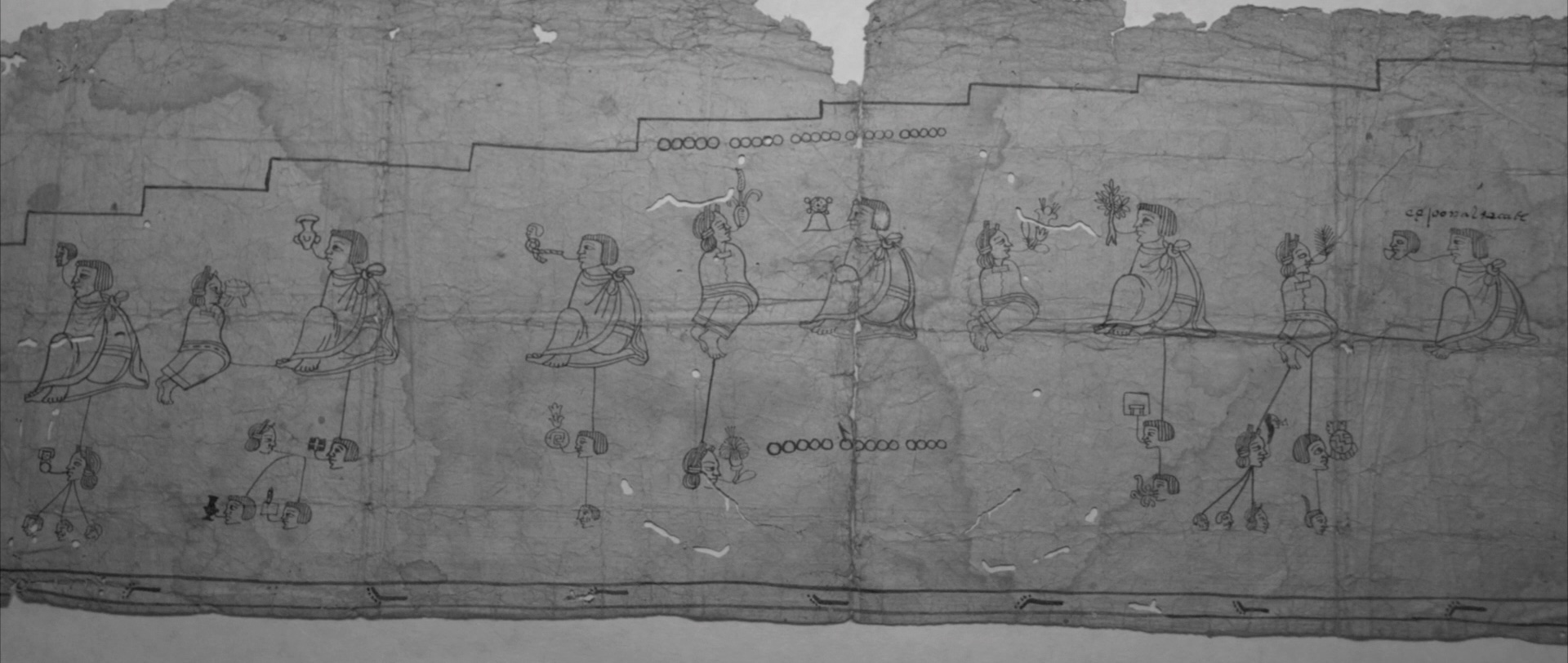

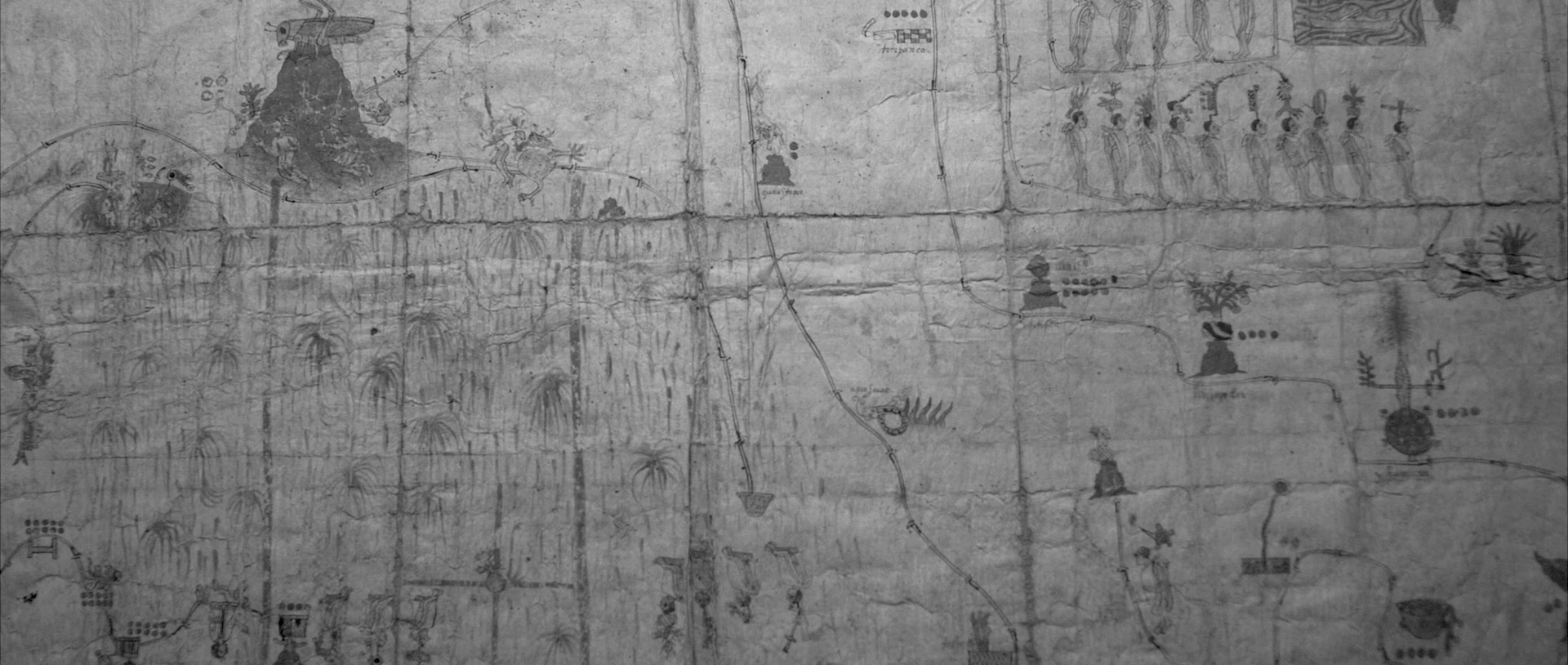

From this global perspective, Mesoamerican codices constitute one of the most complex and sophisticated expressions of Indigenous thought. Before the arrival of the Spanish, various peoples—including the Mexica, Mixtec, Maya, and Purepecha—developed graphic systems that combined images, glyphs, and symbols to record genealogies, histories, calendars, ritual practices, and astronomical knowledge. More than mere documents, the codices were devices of collective memory and tools for maintaining the social, political, and religious order of their communities.

The Materiality of Knowledge: How the Codices Were Made

In Mesoamerica, there was a remarkable diversity of supports and materials for the production of codices, a result of both local availability and deep-rooted cultural traditions. One of the most important was amate paper, produced from the inner bark of trees such as Ficus cotinifolia or Ficus padifolia. This bark was cooked with ash or lime to soften it, then pounded and laminated until a flexible surface was obtained, which became the most widespread writing material among the Nahua peoples and the preferred material for many ritual and calendrical codices.

Another fundamental material was deerskin, used especially by the Mixtecs of Oaxaca, who carefully tanned it and coated it with a layer of white stucco that facilitated the application of pigments. Its great resistance made it ideal for historical and genealogical codices, and several of the most celebrated Mixtec manuscripts were made on this material.

In regions where maguey was abundant, maguey or henequen paper was also used, less common than amate but thicker and more rigid, particularly suitable for administrative documents and possibly for certain early tribute codices. Regardless of the support, a layer of Mesoamerican stucco or gesso—made with plaster or a mixture of calcium carbonate and organic binders—was applied, creating a smooth surface similar to that of the panels used in European manuscripts.

For painting, the tlacuilos used a rich palette of mineral and plant pigments: azurite and malachite for blues and greens, cochineal for intense reds, iron oxides for yellows, ochres, and reds, soot black for lines and outlines, and mesquite or prickly pear gum as a binder. Finally, the pages were assembled with animal or plant-based adhesives to form long, screen-like strips, whose covers were reinforced with wooden boards or hardened cardboard, thus ensuring the durability and proper handling of the codices.

“The tlacuilos, or painter-scribes, not only mastered pigments and ritual iconography, but also the cosmological principles that guided the interpretation of time and the world. Their work had a sacred character, as they reproduced the memory of the gods and the ruling lineages” / Boone, 2016

Social Function: Memory, Legitimation and Power

Mesoamerican codices fulfilled functions similar to those of other ancient writing systems: recording the past, legitimizing elites, and organizing social life. Mixtec codices, for example, recount the history of lineages and political marriages, while the Borgia Group codices guide ceremonies and calendrical calculations. Similarly, Chinese annals, European manuscripts, and Egyptian papyri served to record dynasties, state rituals, and astronomical knowledge essential to the political and religious order.

However, Mesoamerican codices stand out for their intensive use of visual narrative. Unlike the European book, dominated by text, Mesoamerican codices present a simultaneous reading of images, calendrical symbols, and spatial sequences. This characteristic links them, to some extent, to the illustrated manuscripts of Southeast Asia or to Japanese emaki scrolls, where the image plays a central narrative role.

The codices served a wide variety of functions:

- Historical and genealogical: recording dynastic history and political marriages.

- Ritual and calendrical: guiding ceremonies, recording the tonalpohualli (260-day calendar), and divination rituals.

- Economic and territorial: useful for administering tribute, demarcating lands, or recording censuses, examples of which can be seen in some 16th-century Nahua codices.

In highly hierarchical societies, these documents legitimized the authority of rulers and reinforced the continuity of lineages. They also served as guides for daily life: marking auspicious days for planting, marriage, or warfare.

The Colonial Rupture and Hybrid Production

The Spanish conquest caused an irreparable loss: it is estimated that of the thousands of codices produced in Mesoamerica, only about twenty pre-Hispanic examples survive. However, this phenomenon is not exclusive to the Americas. Many ancient traditions have lost a large part of their manuscripts: Egyptian papyri deteriorated due to the climate, and in Europe, entire libraries were destroyed during wars and religious reforms.

In Mesoamerica, in the face of destruction, a hybrid production emerged. Codices such as the Mendoza Codex and the Matrícula de Tributos combine indigenous forms with alphabetic writing, creating a bridge between two worlds. This adaptation has global parallels: in North Africa, Arabic manuscripts were transformed with the arrival of European texts; in Japan, after the opening to European trade, works emerged that blended local techniques with Western influences. These convergences indicate that writing systems are dynamic and that manuscripts evolve in response to radical historical contexts.

Today, institutions such as UNESCO consider Mesoamerican codices part of the documentary heritage of humanity, just like the Dead Sea papyri or the manuscripts of Timbuktu.

The Most Important Mesoamerican Codices

Although thousands existed, only about twenty authentic pre-Hispanic codices survive. Among the most important are:

Borgia Group Codices (Central Mexico)

Among the most important for understanding Mesoamerican religion and the calendar.

Themes: ritual, divination, calendrical.

Format: traditional, screen-folded. Borgia Codex

- Cospi Codex

- Fejérváry-Mayer Codex

- Laud Codex

Mixtec Codices (Oaxaca)

Masterpieces of indigenous painting tradition.

Themes: dynastic histories, genealogies, conquests, and marriage alliances.

Material: stuccoed deerskin.

- Nuttall Codex

- Vindobonensis Codex

- Bodley Codex

Maya Codices

Only four survive, but they are fundamental to Mayan astronomy and cosmology.

Themes: astronomy, rituals, calendrical cycles, Venus observations.

- Dresden

- Madrid

- Paris

- Grolier/Tonalá (currently known as the Maya Codex of Mexico)

Early Colonial Codices of Indigenous Tradition

Although no longer pre-Hispanic, they follow indigenous techniques and iconography.

Themes: They document tributes, political organization, genealogies, and the transition after the conquest.

- Mendoza Codex

- Borbonic Codex

- Tribute Roll

- Toltec-Chichimec History

Codices Today: Revitalization and Identity Pride

Today, codices are studied by archaeologists, linguists, art historians, and Indigenous communities seeking to recover ancestral knowledge. In regions like Puebla, Oaxaca, and Hidalgo, community workshops on traditional painting reinterpret their iconography to strengthen local identity. Likewise, the use of the tonalpohualli calendar and pre-Hispanic cosmology has resurfaced in cultural revitalization movements.

Codices, then, are not just vestiges of the past: they remain a living tool, capable of engaging with new generations and resisting historical fragmentation.

Looking at a codex is to approach a different way of understanding the world. Genealogies, myths, calendars, and paths that connect the human with the divine unfold in their images. Unlike Western linear writing, codices invite us to read in a circular, simultaneous, and symbolic way. They remind us that memory is not limited to words: it is also constructed with colors, shapes, and silences. In a time when information is becoming ephemeral, codices offer us a profound lesson: preserving knowledge is an act of resistance and of the future.

Bibliographic references

- Boone, Elizabeth. Stories in Red and Black: Pictorial Histories of the Aztecs and Mixtecs. University of Texas Press, 2016.

- López Austin, Alfredo and Leonardo López Luján. El pasado indígena. Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1996.

- Caso, Alfonso. Interpretación del Códice Borbónico. Instituto de Investigaciones Históricas, UNAM, 1974.

- Brotherston, Gordon. Book of the Fourth World: Reading the Native Americas Through Their Literature. Cambridge University Press, 1992.